The Oldest Sierra Summit Register

Note on article: The following article was sent as a side bar to Sierra Magazine article by Andrew Beckers titled I Was Here, in the July/August 2008 issue. I received the request from magazine editor Paul Rauber who I had contacted six months prior letting him know that I had rescued the oldest register in the Sierra and was interested in doing an article.

The recent spate of Sierra summit register rip-off and destruction finally pushed me to retrieve the oldest register in the Sierra.

The secret wouldn’t last, but it just might. I‘d kept my mouth shut for fifteen years. I didn’t even tell Steve Roper, my longtime Sierra buddy, where the register was!

I did tell Robin Ingraham Junior. I owed it to Robin. An avid Sierra peak bagger and register aficionado, Robin had figured out that Mount Woodworth might have the original record still in place.

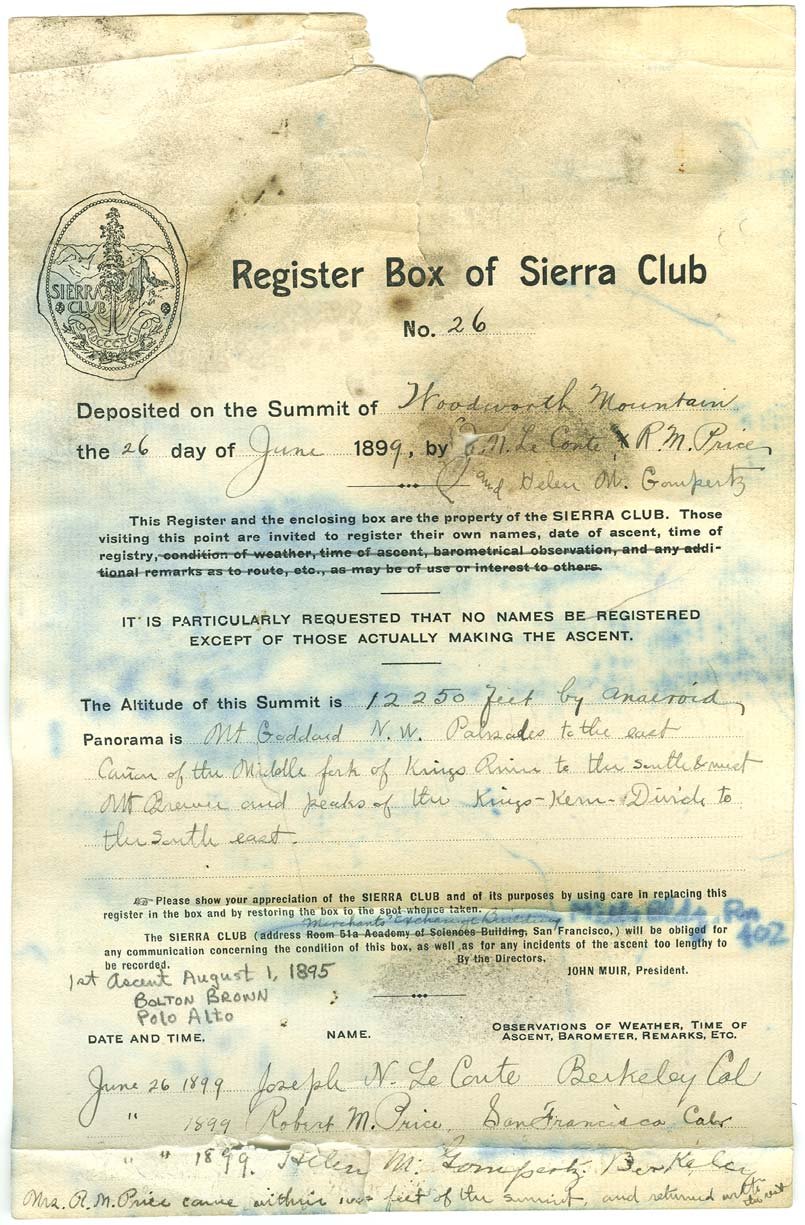

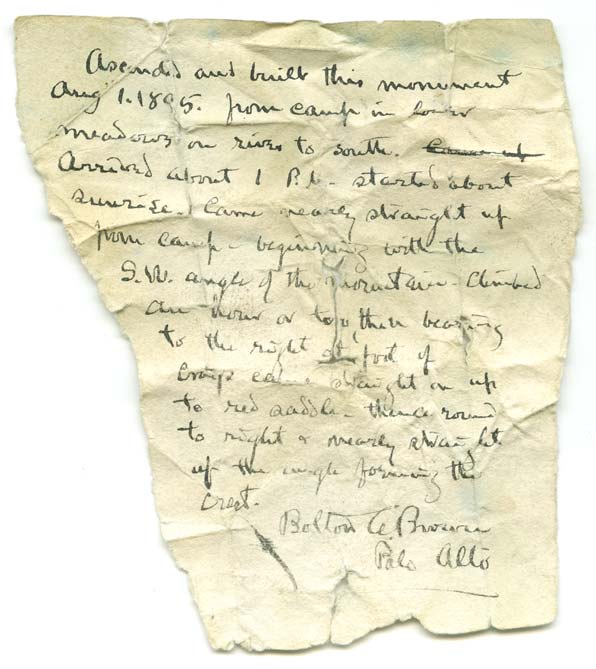

In 1992 my wife, Nancy, and I made a trip to see if Robin was right. The summit itself was nothing special, a Class 2 grunt over some miles of loose terrain. After a few minutes of searching, we carefully opened the metal cylinder and found the frail scrap of paper with Bolton Coit Brown’s signature, route description, and 1895 date. The list of mountaineers in the register was a “who’s who” of Sierra climbing. There was plenty of space left to sign on the pages that had John Muir listed as Sierra Club president. We added our names and left.

Last fall, Robin called to tell me he had seen an internet post that included pictures and a description of the Woodworth register. While we chatted, I googled the website. Sure enough, there was the campsite to campsite account leading to the register! Robin was seething. It was agreed that the register was in peril. Now it’s time to take it down.

But then I hesitated, I needed to button up construction projects for the winter, it had just snowed 6 inches, and the days were short. I didn’t have to care about a bunch of old paper! I finally cut the excuses and drove to the trailhead.

I trudged through slick loose powder up Bishop Pass. Crossing into Dusy basin, there was not a soul in sight this November day. As I traveled, I lost myself in memories of skiing the John Muir Trail and traversing the Devil’s Crags. These youthful adventures had really set the course of my life. I thought of meeting and talking with Dave Brower, Jules Eichorn, Glen Dawson, and Richard and Doris Leonard. Their names preceded mine in the registers; their history blended into mine.

At the summit of Woodworth, I was greeted by an icy blast of wind. Snow grains whipped through the air and drummed the hood of my parka. It was with immense relief that I saw the register. Time for this old thing to get down the mountain before it’s too late.

The time is past when the air was clearer and a register could sit undisturbed for over one hundred years. What’s next, I wondered. What will my daughter see? I jammed my hands into my gloves and headed back to camp.

Claude Fiddler

Crowley Lake

Afterword: Of course after I retreived the register there was a spate of recriminations for the action. For the record I hand delivered the register to the Bancroft Library.

The following article by Robin Ingraham Jr. will decisively round file the arguments against preserving historic Sierra registers at the Bancroft Library

History of Mountaineering Registers in the Sierra Nevada

© Robin Ingraham, Jr., 2008, all rights reserved.

Mt. Woodworth Register, placed in 1899 by Joseph N. LeConte. The historic register remained on the summit for more than 100 years before being removed for preservation in the Sierra Club Archives. (See page 8)

© Robin Ingraham, Jr., 2008, all rights reserved.

This article is dedicated in memory of Mark Hoffman 1960-1988 Who perished in the Devil’s Crags while surveying registers with the Sierra Register Committee.

This manuscript may be printed and distributed ONLY in its entirety. This manuscript may be published by contacting the author for a publication release. Robin4x5@robiningraham.com or grafickman@aol.com

Ghosts in the Clouds

History of Mountaineering Registers in the Sierra Nevada

© Robin Ingraham, Jr., 2008, all rights reserved.

Mt. Woodworth Register, placed in 1899 by Joseph N. LeConte. The historic register remained on the summit for more than 100 years before being removed for preservation in the Sierra Club Archives. (See page 8)

© Robin Ingraham, Jr., 2008, all rights reserved.

This article is dedicated in memory of Mark Hoffman 1960-1988 Who perished in the Devil’s Crags while surveying registers with the Sierra Register Committee.

This manuscript may be printed and distributed ONLY in it’s entirety. This manuscript may be published by contacting the author for a publication release. Robin4x5@robiningraham.com or grafickman@aol.com

Robin Ingraham, Jr.

Introduction

Small weathered books and scraps of paper scattered across the roof of the range contain the history of mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. Most tell stories of only a few recent years, while some still travel back to the distant past of seven decades or more.

Small weathered books and scraps of paper scattered across the roof of the range contain the history of mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. Most tell stories of only a few recent years, while some still travel back to the distant past of seven decades or more.

As a fledging climber in 1985 I sought a climbing companion that shared the same love for steep places I had. Three years before our meeting, Mark Hoffman, a young man with a reputation of soloing remote peaks, had once walked twenty miles into the back country to climb Mt. Stanford alone. His finding the register placed by legendary climber Norman Clyde in 1940 changed Hoffman’s life, and mine. Over the next four years our summers were consumed with nothing but climbing, and seeking the looking glass of time recorded in summit registers throughout the range. On unique occasions we’d stumble upon an old tobacco can holding the names of fewer than ten climbers ascending before us. Other times, the summit would be barren, no trace of previous ascents. That’s not to say that our footsteps were those of a first ascent, but rather indicated the register had somehow vanished, like some apparition of Norman Clyde wandering the cloud-blanketed summits. It was a memory.

During the winter of 1987-88, we were humbled hearing first-hand accounts from climbing pioneers David Brower, Hervey Voge, Jules Eichorn, Dick Leonard, and Marge Farquhar (Francis Farquhar’s widow). During our living room visits and dinners together, we soon learned that a good portion of the Sierra’s history on registers had gone unrecorded. Beside our interest in their personal adventures, we had a great many questions about registers themselves. Who placed the first registers? Where were the Sierra archives? When were they created? Who made the first register boxes? What was the Sierra Club’s position, if any, on register preservation? We listened intensely to each answer and story. During the next decade, each of our new friend’s stories fell silent as time claimed their last breaths.

Over the past 20 years increasing numbers of both registers and Sierra Club boxes have vanished from the peaks. While several authors had attempted to bring light to the problem, none presented any important history on registers. It is at this point that I’ve decided to revisit my files created both from the last of the pioneers narratives and my library. I also wish to thank former Sierra Club Mountain Records Chair Bill Engs for his help filling in some of the historic holes. Without doubt, had this project not been undertaken at this time, many more important pieces to the historical puzzle would have been forever lost.

The First Explorations

On April 21, 1860 the California State Legislature approved the Whitney Survey, named after state’s geologist, Josiah D. Whitney. The purpose of the survey was “. . . to make an accurate and complete Geological Survey of the State, and to furnish maps and diagrams thereof, with a full and scientific description of the rocks, fossils, soils, and minerals, and of its botanical and zoological productions, together with specimens of the same.” (1) They were not seeking mineral deposits to aid gold miners, and they were not mountaineers. Their commission was strictly scientific.

During the first three years of their studies from 1860-1862, survey members carried out their commission throughout California’s interior and coast line. During the summer of 1863, The Whitney Survey made their first ascents in the High Sierra, surveying the topography, climbing, and measuring the heights. Many writers have recounted that the first known register was placed in 1864, but the historical records prove otherwise. Joseph N. LeConte reported,

“Mt. Dana is probably the best-known and most easily accessible of any of the High Sierra summits. It was named by members of the California Geological Survey in 1863 in honor of James Dana, the eminent American geologist. The first recorded ascent was made that same year by Professors Whitney and Brewer and Mr. Hoffmann. In 1889 the original record was still on the summit, and I made a copy of it in my notebook, following exactly the order of the words, and as nearly as possible the style of writing.” (2)

LeConte’s attempt to copy the register in the exact style is also the first known replication of any entry. It is oldest known placed register in the Sierra Nevada, though it has been lost to the annals of time. There is no indication that it was removed for preservation. It merely vanished.

The following summer of 1864 the survey moved south to explore some of the most rugged terrain encountered by white explorers. For the first time, the high mountain regions of the Kern, the Kings, and San Joaquin Rivers were explored and mapped. After spending several weeks approaching the Great Western Divide from the central valley, William Brewer and Charles Hoffmann succeeded in reaching the summit of a 13,600’ peak now bearing Brewer’s name. Of the ascent, he wrote,

“The view was yet wilder than we have ever seen before. We were not on the highest peak, although we were a thousand feet higher than we anticipated any peaks were. . . . Such a landscape! A hundred peaks in sight over thirteen thousand feet – many very sharp – deep canyons, cliffs in every direction almost rivaling Yosemite, sharp ridges almost inaccessible to man, on which human foot has never trod all combined to produce a view the sublimity of which is rarely rivaled, one which few are privileged to behold.” (3)

Two days later Brewer, Hoffmann, and Gardiner again climbed the peak on July 4, 1864. In 1895, Joseph N. LeConte made the third ascent of the peak but failed to find the Survey’s original record as the summit was covered in deep snow. The following summer, LeConte again summited Mt. Brewer and this time located the register. LeConte noted, “It bore the record of but one other climber during the period of thirty-one years. The record remained on the summit for a number years after that; but the fragile paper was broken by continual handling, and it was finally removed to the Sierra Club rooms for preservation, where it was unfortunately destroyed in the fire of 1906”. (4)

Members of the Whitney Survey continued climbing, surveying and mapping the Sierra Nevada until 1870. Four years later, the Survey was officially disbanded when a dispute arose between the legislature and the Survey’s namesake, Josiah Whitney. As the Whitney Survey reached its termination, the Wheeler Survey began visiting the Sierra Nevada and conducted an important body of explorations between 1875-1879. Amazingly, records of their first ascents on Coyote Ridge, and Joe Devel Peak in 1875 are preserved today in the Sierra Club Archives. Although John Muir ascended several impressive peaks during the same time period, he is not known to have left any trace of his presence. Historians know of his ascents only through his writings. Muir’s explorations were of a more personal nature, rather than of a professionally motivated surveyor as were most other explorers of this time period. Despite Muir not leaving registers himself, he became a chief proponent of summit registers after the formation of the Sierra Club in 1892.

The Sierra Club

Two years after the Sierra Club’s creation, the club began making and producing official registers to place on mountain summits.

“In 1894, registers and suitable boxes were prepared for members to deposit on the peaks of the Sierra Nevada. During the summer of that year, registers were placed upon the summits of Mt. Dana, Mt. Lyell and Mt. Conness by Mr. E.C. Bonner; upon Mt. Whitney, by Mr. Corbett; above the Muir Gorge, in the Tuolumne Canon, by Mr. Price; and upon Mt. Tallac. During the summer of 1895,

Messrs. Le Conte and Corbett placed a register upon Mt. Brewer; Messrs. Gregory and Rixford placed the register box (but not the register), upon Mt. Tyndall; Messrs. Taylor and Libby placed one upon Squaw Peak, near Lake Tahoe; and Messrs. Solomons and Bonner placed one upon Mt.Goddard, and one upon Tehipite Dome, on the Middle Fork of the King’s River. …By the directors, John Muir, President.” (5)

The historical record shows that an additional nine official club registers were placed in the next two years. These early registers were a scroll type, rolled and placed first in cast iron tubes, later replaced with brass cylinders with screw tops.

List of the first twenty Sierra Club placed Registers (6)

Mt. Dana – 1894 Tehipite Dome – 1895 Mt. Lyell – 1894 Mt. Stanford (south) – 1896 Mt. Conness – 1894 Pyramid Peak – 1896 Mt. Whitney – 1894 Dicks Peak – 1896 Muir Gorge – 1894 Freel Peak – 1897 Mt. Tallac – 1894 Merced Peak – 1897 Mt. Brewer – 1895 Mt. Florence – 1897 Mt. Tyndall – 1895 Mt. Hoffmann – 1897 Squaw Peak – 1895 Cathedral Peak – 1897 Mt. Goddard – 1895 Mt. Ritter – 1897

Perhaps of curious note on the original scroll type registers was the text, “Please show your appreciation of the Sierra Club and of its purposes by using care in replacing this register in the box, and by restoring the box to the spot whence taken.” What was the purpose of a register? On one hand, registers performed the function of a historical record, principally compiling ascent information and routes, as climbers were asked to “register their own names, date of ascent, time of registry, condition of weather, time and ascent, barometrical observation, and any additional remarks as to route, etc. as may be of interest to others.” On the other hand, early Sierra Club registers provided the organization with more visibility to people of like minded interest; a group of pioneer explorers that together could share ideas and “. . .to render accessible the mountain regions. . .” in holding with its purpose. However, to simply impart registers with route information and Sierra Club promotion would be remiss. The motivation of those carrying and placing the earliest historical registers was not Sierra Club promotion. The early climbers were explorers, challenging themselves physically, while mapping, sketching and providing detailed narratives of their adventures that later helped create trails and associated routes through the Sierra.

During the time of early explorations, regions of the Sierra Nevada appeared on maps as a white wilderness with regions being blank, or containing inaccurate peak locations and rivers. In some cases, peaks were entirely misplaced and ambiguously measured. LeConte explained the trouble early climbers and explorers faced in writing, “The only method of identifying the peaks so named rests on Hoffmann’s map of central California, made at that time. This seems to have based on a compass triangulation, with the details of the river systems very imperfectly represented.” (7)

“Taking the position of the peak as shown on the old map, and correcting this latter for a slight error in coordinates, the position comes out N. Lat. 37 16’ 6”, W. Lon. 118 39’ 6”. Hoffmann evidently fixed the position by triangulation from the San Joaquin-Kings River divide twelve miles to the west, and the topography of the region about Mount Humphreys as shown on his map is of the vaguest sort, having no resemblance whatever to the reality.” (8)

Bolton Coit Brown’s first ascents of both Mts. Ericsson and Stanford illustrate the vague nature of early peak descriptions and their naming from first ascents in 1896.

“Facing now southeast, we scrambled on, up among the wild pinnacles, and at noon gained the summit crag. The elevation seemed about 13,600 feet, and the view, especially to the south down the long and peculiarly straight canyon of the Kern, and to the southeast toward the Williamson-Tyndall group, and southwest to the beautiful, snowy Kaweahs, was extremely interesting and wonderfully beautiful. As it seemed that we were the first to make this ascent, we built a monument and left a record, naming it in honor of Capt. John Ericsson, and in recognition of its extremely craggy character, Crag Ericsson. On the last Sierra Club map it is marked ‘No. 5’.

“The reason we did not name it Mt. Stanford was because from its top we could see that the next mountain to the east – ‘No. 6’ on the Club map – was considerably higher, and therefore we kept this name for it. . . .

“It now became apparent that the summit of this peak is the sharp edge of a thin wall, or curtain of rock, of vast height, and precipitous upon both sides. This knife-edge runs north and south; it may be thousand feet long, sags a hundred feet in the middle, and rises into a point at each end. These ends are very nearly the same height, and the above mentioned monument was at a southern point. But we thought the northern one was a little higher, as it was certainly the natural termination of the promontory, and decided to put the club cylinder there, if possible. . . .

“I built a monument and left in it the Club Register, No. 14, with the name Mt. Stanford upon it.” (9)

It became common during the pioneer era for the USGS to officially recognize geographic names coined in the summit register, as was the case with both Mts. Stanford and Ericsson. Brown’s register remained on the summit for 44 years until it was removed by a Sierra Club group led by Norman Clyde on July 16, 1940. Beside being a mountaineer, Brown was a professor of fine arts at Stanford University and produced a series of near photographic quality drawings of Mt. Clarence King, Mt. Brewer, the Ericsson Crags, Mt. Whitney, and numerous other sketches helping aid other explorers identify otherwise unknown terrain.

Explorations of early pioneers yielded maps, produced feasible routes for trails, art in the form of drawings and photographs, geological descriptions; many gleaned from mountain ascents. In many instances, the mountain ascent was a means to an end: to gain topographical data that would be shared with others. Being a professor of mechanical and hydraulic engineering at U.C. Berkeley, Joseph N. LeConte possessed a mind for detail easily applied to surveying terrain. James Hutchinson, his friend for decades, recalled, “When he was measuring the movement of the Nisqually Glacier on Mt. Rainier he set up his transit and directed me where to drill a long line of auger holes in the ice. I helped him carry his transit and plane table to the summits of many high peaks in the Sierra when he was making observations and rechecking locations for his valuable maps of the Sierra.” (10) In 1899, the Sierra Club Bulletin published LeConte’s table depicting triangulation points between Mt. Ritter to Mt. Whitney and included the longitude and latitudes of each point.

By ascending the high points in the Sierra, LeConte and other explorers were able to fill in the white places, often placing registers upon the summits with route descriptions and related observations. Together with Hutchinson in 1908, LeConte linked a route from Yosemite to the Kings Kern Divide, furthering Theodore Solomons’ dream of completing explorations to establish a high trail the length of the High Sierra, now known as the John Muir Trail.

Around the time of John Muir’s death in 1914, the Sierra Club seemingly experienced a reduced interest in registers. Although the number of official club registers were placed between 1910-1924 declined, many climbers of the era continued exploring and leaving behind a sign of their ascent by stacking rocks into a “cairn”, and often storing small scraps of paper in tobacco cans, sardine cans, or jars to preserve the record of their ascent.

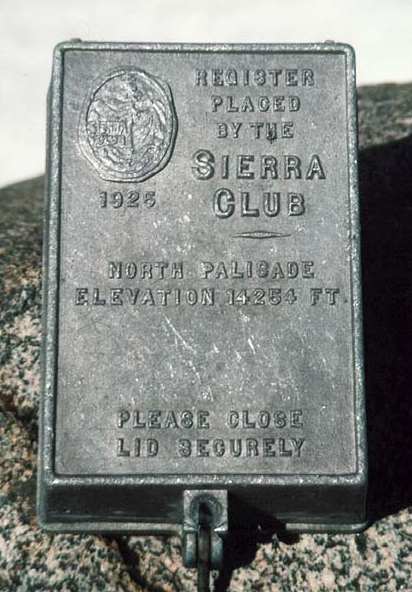

As the Sierra Club’s desire for register placements began fading, a small group known as the California Alpine Club became notably active. On July 15, 1916, the California Alpine Club placed a very efficient and elegant cast aluminum box on the summit of Mt. Whitney. Differing greatly from the official Sierra Club’s scroll type registers, the CAC registers were bound hard back books capable of recording many more years of ascents and protected from the weather and elements much more effectively. Between 1916 and 1926, the California Alpine Club placed 21 cast aluminum boxes with their club logo, name, and hardback books on summits, 11 of which were in the Sierra Nevada. (Unfortunately, this list cannot be published so as to safeguard boxes from theft.) This activity did not go unnoticed and rekindled the Sierra Club’s interest in the mid 1920s.

As the Sierra Club’s desire for register placements began fading, a small group known as the California Alpine Club became notably active. On July 15, 1916, the California Alpine Club placed a very efficient and elegant cast aluminum box on the summit of Mt. Whitney. Differing greatly from the official Sierra Club’s scroll type registers, the CAC registers were bound hard back books capable of recording many more years of ascents and protected from the weather and elements much more effectively. Between 1916 and 1926, the California Alpine Club placed 21 cast aluminum boxes with their club logo, name, and hardback books on summits, 11 of which were in the Sierra Nevada. (Unfortunately, this list cannot be published so as to safeguard boxes from theft.) This activity did not go unnoticed and rekindled the Sierra Club’s interest in the mid 1920s.

In 1924, Casper Kasperson began casting boxes for the Sierra Club to place on peaks in the Sierra Nevada, and other summits throughout the Western United States. The historical record shows that the first Sierra Club box with hardback book was placed on Glacier National Park’s Mt. Cleveland during the club’s annual High Trip. (11) The boxes were similar to the CAC boxes, but included both the peak’s name and elevation. The following summer a dispute between the Sierra Club and the California Alpine Club began brewing. In 1925 the Sierra Club placed a box on North Palisade and relocated the CAC box to a lower peak in the Palisades. Over the forthcoming years, the action again occurred on Mt. Whitney, Mt. Lyell, Half Dome, Mt. Brewer and University Peak as the Sierra Club placed and relocated the CAC’s boxes, much to the California Alpine Club’s vocal dissent. Ultimately, the California Alpine Club relinquished to the Sierra Club the responsibility to place and maintain registers largely due to the Sierra Club’s size and therefore greater ability to take care of this need.

Establishing the Sierra Club Archives

Since the Sierra Club’s creation in 1892, trip leaders, some of which were Sierra Club presidents, and its members had long been removing registers for preservation found to be either full, or clearly in peril of loss caused by the weather and elements. Such was the case with the second placed register in the Sierra, as LeConte explained, “. . .the fragile paper was broken by continual handling, and it was finally removed to the Sierra Club rooms for preservation . . .” (12) In 1929, the problem of having no official repository for historic mountaineering items and other club materials was addressed at the club’s board of directors meeting. In the 1930 Sierra Club Bulletin, William Frederic Bade wrote,

“At the last Directors’ Meeting formal steps were taken to provide for the establishment of Sierra Club Archives into which may be gathered, for systematic arrangement and permanent preservation, the immensely valuable historical materials which now exist in the form of private personal collections, or lead an obscure and precarious existence in the attics and trunks of our widely scattered membership. A committee (Bade, Farquhar and Dawson) has been appointed and a beginning is now to be made to bring these materials together for safe keeping. . . .No other organization includes in its membership so many pioneer explorers of these wildernesses as the Sierra Club, and it, therefore, is in a peculiarly favored position to undertake the assembling and salvaging of historical documents of pioneer days. Unless this task is seriously undertaken at once many unique opportunities will be lost forever.” (13)

Over the decades, the Sierra Club has gathered important writings, and documents of its explorers and mountaineering history into what is perhaps the most impressive collection in the United States. Despite the fact that some contemporary climbers disagree with the premise of removing a register for any reason, citing the loss of the Brewer register in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire, there is no denying the facts of what the Sierra Club’s valiant efforts has preserved. Within the club’s Mountain Summit Registers Collection are six original registers placed by the survey teams dating back to 1875, 14 Sierra Club registers placed during the 1890s, and a remarkable wooden register Theodore Solomons found atop Tehipite Dome in 1895. Without question, had the Sierra Club not taken formal steps to preserve this unique mountaineering history in one collection nearly all would have certainly been lost either to private collections (private archivists or thieves), or lost to decay. The Sierra Club Archives continued to be protected in a fire proof area by the Club until all registers were transferred to the protection of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. (14)

Climbers Guide to the High Sierra

Despite the fact that the Sierra Club had been compiling route information for nearly forty years, a formal effort to compile information into a Climbers Guide did not occur until 1932 when Dick Leonard found a record of a climber claiming a second ascent on Mt. Starr King about 55 years after the third ascent! Over the next five years, Dick Leonard compiled route and ascent information obtained from mountaineering notes and articles in the Sierra Club Bulletins, and reports from other climbers gathering information from registers on peaks at the time. One of history’s greatest surveys of registers occurred in 1934 when David Brower and Hervey Voge undertook their famous Knapsack Survey of Routes and Records. During their lengthy adventure beginning on May 20, 1934, the pair hiked over 200 miles in 67 days, and ascended 59 peaks; 32 of which were first ascents. Amazingly, some climbers today still have the rare thrill of stumbling upon one of the registers placed during their sojourn. Thanks to climbers like David Brower, Hervey Voge, Norman Clyde, Jules Eichorn and Glen Dawson climbing and reviewing register entries, Dick Leonard’s 1937 publication Mountain Records of the Sierra Nevada contained ascent and route information on 890 peaks. Over subsequent years, active climbers of the period authored numerous articles in Sierra Club Bulletins on route descriptions and established the class 16 rating system. In the early 1950s the Sierra Club handed Hervey Voge decades of research with the task of assembling the first A Climbers Guide to the High Sierra, published in 1954.

The Search for Walter A. Starr, Jr.

During the time that Leonard was compiling route and ascent information, Walter A. Starr, Jr. was working on compiling trail information, later published as Guide to the John Muir Trail and the High Sierra Region. Starr had gained a reputation as a hiker and climber of incredible speed and agility. Starr’s journal records that he once hiked 143 miles of mountain passes and trails in four days. As he neared the completion of his research, Starr went missing.

On August 7, 1933 Walter A. Starr, Jr. failed to meet his father at Glacier Lodge, and when not returning home on the 13th from his scheduled climbing vacation in the Sierra Nevada it was obvious something had gone terribly wrong. After locating his car at Agnew Meadows, a search and rescue team of leading climbers was organized to find the missing climber. Soon Starr’s vacant tent was found at Lake Ediza, and several mountaineers began searching the Ritter Range. On August 16, Douglas Robinson, Jr. and Lilburn Norris ascended Mt. Ritter and on the summit “. . .found that Starr had registered there on the 31st of July, saying that he had used crampons and ice-axe, having crossed the glacier. As both were in his camp, it was evident that he had returned safely from Ritter.” (15) Other searchers climbed Banner Peak and Clyde Minaret, yet found no indication of Starr’s ascent in the registers. Although no ascent on Clyde Minaret could be verified in the register, signs of the missing climber were evident through freshly built ducks as route markers. The search teams also ascended Michael Minaret, and found no record of Starr’s ascent in the register, though the following year Jules Eichorn discovered Starr’s entry on a faded piece of cardboard. It was just missed during the search. After nearly a week of climbing the Minarets, reading the existing registers and searching the regions below the peaks, all but Norman Clyde abandoned the search. A few days later Clyde found the fallen climber high on Michael Minaret. While the registers did not yield the clues that ultimately led to finding Starr, his entry on Ritter provided some evidence where not to look. Registers were a key tool the group used for both clues and a process of elimination, and remain a tool Search and Rescue teams employ when sleuthing evidence for missing climbers.

Different Types of Registers

Throughout the decades registers have undergone an evolutionary progress. Since most registers have not been placed by an organized effort, many consisted of only scraps of paper left in rusty tobacco cans, sardine cans, jars, or whatever was available. Due in part to the fact that Norman Clyde made more Sierra Nevada ascents than anyone else at any point in history, Clyde likely placed more registers than any other climber. It was common during the 30s, 40s and 50s for climbers to ascend a peak, believing it to a first ascent, only to discover Clyde’s signature in a rusted can. Today, most of the cans are now gone. Unfortunately, many cast aluminum boxes have been stolen and will likely not be replaced due to expense. In their absence, the Sierra Peaks Section (SPS) often provides the cast aluminum cylinders that climbers are familiar with today. The SPS maintains registers and containers on the 248 peaks on their list.

One of the most remarkable pieces of climbing history was discovered by this author in 1989 on an unnamed peak identified as Peak 12,560+ .75 S of Rodgers. Found buried on the barren summit was a rusty can containing the names of the first ascent; Ansel Adams, Cedric Wright and Willard Grinnell 1924. The delicate paper was frayed and burned by lightening strikes and so was near loss so that it was removed for preservation in the Sierra Club Archives. While becoming increasingly rare, climbers today still occasionally find registers dating to the 1920s and 1930s placed by Norman Clyde, David Brower, Hervey Voge, and Jules Eichorn in old rusted cans.

One of the most remarkable pieces of climbing history was discovered by this author in 1989 on an unnamed peak identified as Peak 12,560+ .75 S of Rodgers. Found buried on the barren summit was a rusty can containing the names of the first ascent; Ansel Adams, Cedric Wright and Willard Grinnell 1924. The delicate paper was frayed and burned by lightening strikes and so was near loss so that it was removed for preservation in the Sierra Club Archives. While becoming increasingly rare, climbers today still occasionally find registers dating to the 1920s and 1930s placed by Norman Clyde, David Brower, Hervey Voge, and Jules Eichorn in old rusted cans.

Until recently, a register exceeding 100 years resided on a wind swept summit. In 1992 Claude Fiddler discovered the records of both the first ascent by Bolton Coit Brown in 1895, and the Sierra Club scroll housed inthe brass tube placed by Joseph N. LeConte in 1899 on Mt. Woodworth. Finding that the register was neither full or weather damaged, Fiddler left the register on the summit, telling no one but this author. The historic register remained on the summit until this author discovered that a trip jointly sponsored by the Sierra Club Angeles Chapter’s Ski Mountaineering Section and Sierra Peaks Section had found the old register and subsequently posted photos of the document on the Internet. (16) Fearing that this easily gleaned information placed the 100+ year old register in increased peril of loss to thieves, Fiddler again made the twenty plus mile hike and removed it for preservation in the Sierra Club Archives. At the time of this research (2008), it can be stated with near certainty that all of the original scroll type Sierra Club registers housed in brass cylinders have been removed. Likewise, nearly all of the hardback books placed in cast aluminum boxes during the 1920s, 30s and 40s have been removed from summits. Many can be accounted for in the Sierra Club Archives, while sadly many others have merely vanished. While many climbers today believe that there is no clear policy on register removal or preservation, the historical record shows that there is. All one has to do is look to past precedent.

Record of the first ascent of Mt. Woodworth placed by Bolton Coit Brown in 1895. This record of the first ascent, along with the Sierra Club register placed by Joseph N. LeConte in 1899, remained on the summit for more than 100 years.

– Page 8

History of Mountaineering Registers in the Sierra Nevada

Register Removal Policies, and Missing Registers

When formally establishing the Sierra Club Archives there was really no need to put in writing a register removal policy, that is, whether should a register remain on the summit forever or should it be preserved. There had been such a long lineage of climbers removing registers that were either full or clearly in peril of loss caused by the weather and elements there was no dissenting opinion found in the early historical record. Joseph LeConte, Theodore Solomons, Francis Farquhar, William Colby, and Norman Clyde had all removed registers for preservation.

The policy on register removal has been spelled out by the Sierra Club Mountaineering Committee in several of their annual meetings. “Engs briefed Dennis Lantz that Bancroft is the official repository for filled original registers (copies of such replaced on summits), historical artifacts having to do with summits, and other important summit materials subject to theft or summit exposure” (17) “The policy is to send them to Mills Tower when filled. Marshall Kuhn (The Sierra Club Historian) ships them to Bancroft Library after making copies”.

(18) (Author’s note – removed registers are no longer sent to the Sierra Club, but rather directly to the Bancroft.) In 1963, Sierra Club Mountaineering Committee Mountain Records Chair Bill Engs wrote, “If you feel the register will not last another season, it should be replaced, even though it may not be full. Ideally, the person removing a register would have with him an official replacement.” (19) Bill Engs served as the Mountain Records Chair from 1962-1973.

Over the decades some registers have been merely lost to decay while countless others have vanished at the hands of souvenir hunters or taken by others believing that registers are trash and don’t belong on peaks. In 1987 the hands of fate, as it would be, drew this writer and Mark Hoffman into historical record, generating a renewed register preservation project.

On July 27, 1987, Mark Hoffman and Robin Ingraham, Jr. ascended Midway Mountain in the Great Western Divide, filled with enthusiasm to see the historic 1912 register described in Steve Roper’s A Climbers Guide to the High Sierra, 1976. It was nearly a race to see who could hold the register first. At the 13,600’ summit Hoffman dug through the rocks to unearth the container, then slid off the lid. The old register was gone. Over the next ten minutes they carefully read each entry in the 1969 register until finding the evidence they’d been dreading. A 1979 entry by a group calling themselves “The Purple Mountain Gang” (PMG) wrote, “Note the turkey’s with the mountain numbers in the original register, which Sierra Clubbers must think is missing, but which we stole.” They signed, Mark Farkel and Otis Jasper Russell.

This wasn’t the first time Hoffman had seen the PMG’s less than noble activity. Four years earlier he’d climbed Mt. Dade and found the PMG had taken the Dade register and replaced it with a register from a Colorado summit. Hoffman vividly recalled the story about the Purple Mountain Gang’s boast of the “Register Exchange Program” in which they’d taken registers from other summits and switched them to other peaks.

Angered over the Midway theft, Hoffman and Ingraham set out on a quest to recover the register and bring the thieves to justice. For weeks they made call after call to the Sierra Club since this was a Sierra Club placed register. Hoffman finally contacted executive committee member, Michael McClosky, who was sympathetic about the loss, but stated that pursuing these problems was beyond the Sierra Club’s current scope. The Sierra Club’s help was a dead end. They then contacted the Chief back-country Ranger of Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks, Paul Fodor. Unfortunately, Mr. Fodor echoed the same sentiment. The National Park Service is not well enough staffed to pursue theft of mountaineering artifacts. Sorry.

Formation of The Sierra Register Committee

In 1988 Mark Hoffman called David Brower at his Berkeley home and discussed the current problems. Being sympathetic and helpful, Brower invited Hoffman and Ingraham to meet with him in February. The privilege to meet one of the Sierra Nevada’s last generations to explore and climb the last un-climbed places was overwhelming. Brower’s advice is what truly formed the Sierra Register Committee (SRC). As an advisor, he recommended a six part program focusing on education and preservation of existing historic registers. His urging was underpinned with the statement, “If you guys are truly upset about this, you’ll do something about it instead of making a bunch of noise. The world is full of noise makers, but short on activists.” During the following months Hoffman and Ingraham met other Sierra pioneers, Jules Eichorn, Hervey Voge, Dick Leonard, and Marge Farquhar. Each one echoed Brower’s sentiment that something needed to be done and each pioneer reinforced and endorsed the project. The Sierra Register Committee did not invent anything new, but rather implemented the policies and practices of the early Sierra Club.

A Six Part Program

Under the advice of Brower, Eichorn, Leonard, Voge and Farquhar, the six part program was drafted as follows:

- Register removal criteria, formed by David Brower. Remove historic registers which are either full or in peril of loss caused by the weather and elements. In peril of loss is generally a condition of badly damaged, but can pertain to a published location of a significantly old register. Registers removed for preservation are to be placed in the Sierra Club Archives since this was the Club’s long standing tradition stemming from the turn of the twentieth century under John Muir and his fellow explorers. The current location for the archives is UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library.

- Anchor all register boxes to the summits to prevent their theft. (Register boxes were being stolen as well.)

3. Manufacture new aluminum register boxes to place on summits.

- Upgrade all deteriorating register containers to increase longevity. PVC (plastic tubes) was commonly used, but boxes were placed whenever possible. (It was later discovered, however, that some containers became wet inside, and others did not. Uncertain as to why. The PVC containers were abandoned after two years.)

- Place instructional cards in all historic registers to increase awareness about the Sierra Club Archives. These cards increase the odds for proper preservation of registers removed by other concerned climbers. The idea here was that many climbers removing registers were well intentioned, but couldn’t find out where to send registers for preservation.

6. Place photocopies of historic registers on the summits from which they came.

The pair undertook this project without any outside financing and in their first year expenses exceeded $200; due largely to photocopy expenses of registers removed over 30-50 years earlier.

The drafted plan of the activities under the Sierra Register Committee was endorsed additionally by the National

Park Service and included a written and signed Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between Robin Ingraham, Jr. and Superintendent of Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks. Verbal endorsements were provided by Ron Mackie, Yosemite Chief Back-country Ranger. The Forest Service didn’t see the need for an MOU.

During their first summer of activities Mark Hoffman and Robin Ingraham, Jr. spent numerous weeks climbing throughout the Sierra in search of historic registers, not much different than Voge and Brower 54 years earlier. Tragically, on August 11, 1988, a rock slide swept Hoffman down a steep chute on Devil’s Crag No. 8, then over a 50 foot cliff to his death. The story is well chronicled in Eric Blehm’s 2006 book, The Last Season. (20)

In the winter of 1988-89, Mark Marden, one of Sierra magazine’s editors, penned an article for the Jan/Feb 1989 publication outlining Hoffman’s untimely death and goals of the SRC. Unfortunately, Marden’s article did more harm than good as he omitted the fact that the SRC was created only after careful consideration and consultation with noted Sierra pioneers. Furthermore, Marden did not delineate the fact that the SRC had clearly defined removal criteria, full or in peril of loss, but rather wrote that whenever finding an old register they removed it for preservation in the Sierra Club Archives. The omission and misleading information generated a very uncomfortable dispute with a Southern California group of Sierra Club climbers belonging to the Sierra Peaks Section.

The Arising of a Dispute

In the spring of 1989, Ingraham received a call from Bill Oliver of the Sierra Club Angeles Chapter’s Sierra Peaks Section (SPS). While Mr. Oliver was sympathetic to the cause, he informed Ingraham that many members of the SPS were not happy with the SRC’s activities to remove registers. The SPS, the largest group of Sierra climbers, has a list of 248 peaks that their members seek to climb. Furthermore, the SPS had been placing registers on these summits and according to their bylaws at the time advocated a position that registers be left on summits forever. Under Article 7, “Summit registers will be left in place on the peaks. Additional or larger containers will be provided when there is insufficient space in the existing container. . . .Notebooks with historical significance may be preserved by copying. The original should be returned to the peak within a year. . . .” To attain a modern consensus on register issues, the SPS conducted a members’ poll on registers published in The Sierra Echo.

Although a clear majority of respondents, 71%, favored leaving registers on the summits in accordance with SPS bylaws, disseminating the data becomes complicated when respondents were asked if the SPS should join forces with the SRC which produced a nearly deadlocked 50/50 split. (21)

A separate study conducted by Robin Ingraham Jr. and Mark Tuttle gained entirely different results. Between December 1, 1989 and April 1, 1990, Ingraham and Tuttle conducted the Yosemite Rock Climber Survey to attain a consensus on rock climbing issues at the time, and also asked a single mountain question, “Should full and weather damaged historic summit registers be removed to preserve for future generations (in public library), or should they remain on the peak where subject to disintegration and loss?” 587 surveys were sent to Climbing subscribers in Central California, and 387 sent to American Alpine Club members in California. Of the 1,243 surveys, 587 were returned, with results of 65% preserve, 15% Leave on Summit, 20% undecided.

During the Autumn of 1989 Ingraham attended a Sierra Club Mountaineering Committee meeting and got into a heated debate with several SPS members concerning register removal. Seeing the continuing rift over register issues, Bill Oliver, a former SPS Chair, tried to mitigate the conflict by writing several articles printed in SPS newsletter, The Sierra Echo. In the February 1992 issue, Oliver wrote an article titled “The Bancroft Library” in an attempt to calm the situation. Quoting from Oliver’s manuscript with his permission,

“It would surely be more satisfying to read the original old register on the summit rather than as part of a collection in a library. The reality, of course, is that none of the Sierra registers is known to have come from the Planet Krypton. At some point, assuming it is not first stolen or vandalized, the register will either be lost to wear and tear or rescued from further wear and tear. On a climb of Devils Crag #1 last October, I detoured to ascend White Top, the peaklet just north of the Crags ridge. Sheltered deep within the elaborate summit cairn, I spied what turned out to a rusty old tobacco tin. There was no joy and no satisfaction and no sense of naturalness in having its paper contents partly crumble in my hands. Had I tried to unfold the small sheet, it would have disintegrated. I would rather read something still legible in the Bancroft Library.

“Summit registers have been rescued from mountains since soon after the advent of our alpine sport. This is not an activity that the Sierra Register Committee, or the Sierra Club, recently invented. The Club has been, at least haphazardly, removing old registers since before the turn of this century. Back in the ‘30s, during the ‘Golden Age of Sierra Club Mountaineering,’ there was, indeed, a concerted effort to bring in the then old registers, as well as to place new boxes and books on the major peaks.

“In more recent times, deteriorating registers have been removed far less by plan than by unexpected discovery of their sad conditions. . . . Just this past August (1991) another SPSer, while on a CMC trip, unexpectedly removed the old Devils Crags #1 register when its badly deteriorated condition was revealed to him. The book was subsequently turned over to the SPS Mtn. Records Chair. . . .In October I (Bill Oliver) returned a full-size copy with a historical background sheet, to the summit.”

At the direction of the SPS Management Committee, in April 1992 Bill Oliver mailed the Devils Crag #1 register (1933-1977) and Mt. Starr King register 1931-1936 (found in the SPS records collection) to the Bancroft Library. During the early 90s, the SPS amended their bylaws on peak registers to read, “A register should not be removed, even if full, when less than 40 years old, unless it is seriously weather damaged and in danger of loss. A register may be removed for preservation if it is 40 years old or older and full. . . . Notebooks with historical significance shall be preserved by copying with a digital camera in place.” (22) Despite the official policy change, there remains a wide spread perception that most SPS members still favor leaving registers on the summit indefinitely. There is no additional data to verify current SPS sentiment.

Although some the friction between the SPS and SRC was slightly diminished, both the loss of his best friend, Mark Hoffman, and being left alone to organize the group of climbers proved too much. Ingraham abandoned climbing in 1994 and without his leadership the SRC disbanded.

Three Divergent Views on Registers

Beginning around 1970, three divergent views on what to do with registers began to arise.

1. Registers should be removed for preservation. The argument of preservation is as follows: Registers are not a natural occurring part of the landscape. They are historic artifacts documenting human activity. Since they were placed by man, it is man’s responsibility to preserve these documents for future generations. The idea of leaving a register on a peak forever would be like deciding to leave the Dead Sea Scrolls in their Mediterranean cave “forever”, to eventually decay. Since societies throughout history have sought to preserve historic items, one must question why an original piece of mountaineering history, in this case a register, is any different form any other sociological artifact? Timely register removal for preservation is in line with the long standing Sierra Club tradition, and validated by the mountaineering committee.

Jules Eichorn put it very well when articulating his views on register policies:

“Saving historic peak registers by removing them from the summits (when full or damaged) and placing them in the Sierra Club Archives at the Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley, has been and is the safest and most satisfactory way to preserve these registers. Mountain summits which experience great storms cannot, in my mind, be a better place to preserve registers. Since these originals are valued pieces of mountaineering history, it doesn’t seem logical to simply copy this material and return the original to the summit for it will eventually become lost. Originals should be preserved for future generations. Thus, after timely removal, the guidelines set by Robin Ingraham, Jr. of the Sierra Register Committee may be well observed in the spirit of conservation. By following such guides, registers will

be removed before the information is destroyed.” (23)

- Registers should be left on summits forever. Some climbers believe registers belong on the summits forever, no matter what their condition becomes so that future generations can enjoy them. It doesn’t mean something in a dusty old library. All we can do is hope that they are not destroyed by the weather or stolen. With some certainty, this author believes that we would all rather read the original on the summit, but the idea crumbles when one follows the thought to the conclusion. Leaving a register on a peak forever is nice sentiment, but one not grounded in reality. To use a metaphor, follow the paper trail. Even if theft were not a problem, paper still disintegrates. Furthermore, if it disintegrates then no future generations can enjoy them anywhere.

- Registers should be removed and discarded. This is the radical environmentalist view. Some people believe that registers are trash and should be discarded. This position flies in the face of the historical relevance of the document and holds an elitist view of purity. These are the same types of people that pry USGS markers from summits: that is essentially theft and vandalism.

In a letter addressed to the Sierra Register Committee, two climbers summed up their anti-register message in writing,

“For many people registers are an offensive intrusion on the wilderness experience. Many people are removing registers because they are just more garbage on the mountain. Many find that registers a relic from the ‘conquest era’ of climbing, that they are a waste of resources and are visually offensive. The historical aspects of registers is important – preserve them in a museum, not on our mountains. Putting more registers is repugnant to many’s wilderness experience. Anchoring them to mountains is a total intrusion on the wilderness and is notappropriate. As long as people insist on putting garbage on the mountains, we will continue to pick up that garbage!” Signed D.F. King, and C.F. King.

Verifying the Current Problem of Theft

Over the last 14 years the problem of stolen Sierra Club boxes and historic registers dating to the 1920s has escalated. While it is impossible to know how many registers have actually been stolen, a yardstick of the problems can be applied by counting the number of stolen register boxes. In total, the Sierra Club is estimated to have placed 60 register boxes, although only 49 in the High Sierra can be verified. Of the 49 verified Sierra Club box placements, 26 Sierra Club boxes have been stolen, and in some cases, the box and historic register have vanished together. Specific instances can be cited in the thefts of the Sierra Club register and box placed on Mt. Barnard in 1936, and 1940 register and box placed on Thunder Mountain.

The list of 26 stolen Sierra Club boxes (likely incomplete)

| Clouds Rest | *Mammoth Mountain | Mt. Stanford (south) |

| North Dome | Mt. Agassiz | University Peak |

| Half Dome | North Palisade | Milestone Mountain |

| Unicorn Peak | Thunderbolt Peak | Thunder Mountain |

| Cathedral Peak | Mt. Goddard | Mt. Gould |

| Lembert Dome | Mt. Darwin | Mt. Barnard |

| Fairview Dome | Mt. Humphreys | Mt. Tyndall |

| Mt. Dana | Mt. Williamson | Mt. Muir |

| Mt. Conness | **Mt. Langley |

*On display at ski area gondola house – technically not stolen **On display in the Eastern California Museum, Independence – technically not stolen

The total number of stolen boxes and registers doesn’t just end with Sierra Club boxes and registers. In addition to Sierra Club placements, the California Alpine Club placed 11 boxes, and the Sierra Register Committee placed an additional 29 boxes in the Sierra. Merely figuring an additional ten box thefts swells the estimated stolen box total between 35-40 at this time. (24)

In recent years numerous people have posed the question, who is stealing boxes and registers? While the answer is elusive, it appears that a few climbers are bent on merely removing both registers and boxes as either trash or collectibles. Recently, a Sierra Club box once thought to be stolen was found buried in the dirt at a high base camp. Since the box is planned to be taken back to the summit, the geographic reference must be protected. In another odd twist, a climber reported in August 2008 that she had encountered an older gentleman who claimed that he was a box collector. Some might call it harmless “collecting”, but stealing boxes is a violation of the Antiquities Act. The only clue we have at this time is that the collector claimed his father climbed with Hervey Voge. Beyond this, the trail runs cold.

We must all be more sensitive to protect the few remaining historic registers in the Range of Light. Given the current problems, publishing locations of historic registers, either in magazines or on the Internet, could be considered questionable judgement; potentially resulting in more lost history. Despite being asked not to divulge the location of historic registers, one writer recently published a story revolving around a 1924 register currently on a Sierra peak. He is not alone. Unfortunately, other climbers have posted photographs of historic registers on the Internet. In light of the current problem all we can truly do is be vigilant about discouraging other climbers from publishing photos and written descriptions of where old registers are located.

The signature of Norman Clyde, the greatest of all Sierra mountaineers, can still be found atop a few summits, at least for a while. Some day they all will be mere memories. Within the next twenty to thirty years most original registers will likely be removed for preservation in the Sierra Club archives, decayed, or stolen. Either way, the era is ending when we can look back in time to when first ascents were being made. The oldest registers will soon vanish from peaks, like ghosts in the clouds.

Reference Source Notes:

- (1)

- Whitney Survey, Geology, Vol. 1

- (2)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1922 Vol. XI, No. 3, p. 246

- (3)

- Brewer, William, Up and Down California, p. 524-525

- (4)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1922 Vol. XI, No. 3, p. 252

- (5)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1896 Vol. I, No. 8, pp. 337-338

- (6)

- Engs, Bill, “The Saga of the Registers”, unpublished manuscript.

- (7)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1922 Vol. XI, No. 3, p. 245

- (8)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1922 Vol. XI, No. 3, pp. 249-250

- (9)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1897 Vol. II, No. 2, pp. 92-94

- (10)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1950, p. 2

- (11)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1925 Vol. XII, No. 2, p. 156

- (12)

- Ibid.

- (13)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1930 Vol XV, No.1, p. 97

- (14)

- Sierra Club Mountaineering Committee minutes, April 29, 1972.

- (15)

- Sierra Club Bulletin 1934, Vol. XIX, No. 3, p. 82

- (16)

- <http://www.angeles.sierraclub.org/skimt/trips/columbine03/Columbine204.htm>

- (17)

- Sierra Club Mountaineering Committee Minutes April 28, 1973

- (18)

- Sierra Club Mountaineering Committee Minutes 5/4/1974

- (19)

- Sierra Club Bulletin, June 1963

- (20)

- Blehm, Eric, The Last Season, 2006 1st Ed., pp. 160-167

- (21)

- The Sierra Echo Nov.-Dec. 1989

- (22)

- Peak Registers 8.0 <http://angeles.sierraclub.org/sps/mancomprocedures.html#recordsl>

- (23)

- The Sierra Echo Jan.-Feb. 1990 EICHORN QUOTE A scan of Eichorn’s original letter can also be found at: <http://robiningraham.com/Mountaineering/JulesEichornLetterOnRegisterPreservation.jpg>

- (24)

- The stolen box list was compiled through a personal discovery of Sierra Club boxes placements, with additional placements noted through both the Sierra Club’s Mountain Records provided by former mountain records chair Bill Engs, and noting hard back books in the Sierra Club Archives. Having a compiled list of box placements, thefts could be established through climber’s reports of missing boxes, and others verified missing through Internet sources as “Sierra Peaks Summit Register Needs”. <http://www.climber.org/data/SierraPeaks/RegisterNeeds.html>.

- (1)

- Removed registers should be sent to:

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION:

The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, CA, 94720-6000. Collection Title: Sierra Club Mountain Registers and Records. Collection Number: BANC MSS 71/293c. Telephone number: 510-642-6481

The Sierra Club Mountain Registers Collection is available for public review. Please contact the Bancroft Library prior to your arrival so that the material can be retrieved from archival storage.

(2) At the time of this writing, the SPS Mountain Records Chair has indicated that removed boxes and containers can be returned anonymously to the SPS to be returned to the summits with no questions asked, and with no consequences.